-

A Post-mortem on the Mental Model of a System

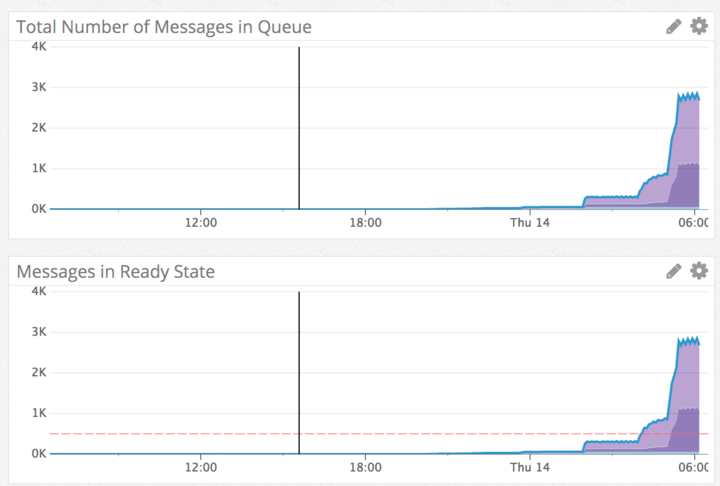

On Thursday, December 14th we suffered a small incident that lead to various user notifications and actions not being triggered as they would during normal system operations. The issue was caught by alerting so that staff could react prior to customers being impacted, but the nature of the failure and the MTTR (approx 4 hours) was higher than it should have been given the nature of the error and the corrective action taken to resolve it. This seemed like an opportune time to evaluate the nature of the issue with regards to our mental models of how we think the system operates versus how it actually operates. This post-mortem is much more focused on those components of the failure than our typical march towards the ever elusive “root cause”.

Below is a timeline of the events that transpired. After that we’ll go into differnet assumptions made by the participants and how they’re unaligned with the actual way the system behaves.

Timeline

- Datadog alert fires stating that the activity:historyrecordconsumer queue on the RabbitMQ nodes is above thresholds.

- Operator on-call receives the alert, but doesn’t take immediate action

- Second Datadog alert fires at 5:37am for direct::deliveryartifactavailableconsumer-perform

- Operator is paged and begins to diagnose. Checks system stats for any sort of USE related indicators. The system doesn’t appear to be in any duress.

- The operator decides to restart the Sidekiq workers. This doesn’t resolve the issue, so the operator decides to page out to a developer.

- The operator checks the on-call schedule but finds the developer on-call and the backup-developer on-call have no contact information listed. With no clear escalation path on the developer side, the operator escalates to their manager.

- Management creates an incident in JIRA and begins assisting in the investigation.

- Manager requests that the operator restart the Sidekiq workers. This doesn’t resolve the issue.

- Developers begin to login as the work day begins

- Developer identifies that the work queues stopped processing at about 2:05am

- Developer suggests a restart of the Consumer Daemon

- Operator restarts Consumer Daemon

- Alerts clear and the queue begins processing

As you can see, the remedy for the incident was relatively straight forward. But there were a lot of assumptions, incorrect mental models and bad communication that led to the incident taking so long to be resolved. Below is a breakdown of different actions that were taken and the thought process behind them. This leads us to some fascinating insights on ways to make the system better for its operators.

Observations

Some brief context about the observations. The platform involved in the incident has recently been migrated from our datacenter hosting provider to AWS. Along with that migration was a retooling of our entire metrics and alerting system, moving away from InfluxDB, Grafana, Sensu to Datadog.

The platform is also not a new application and precedes the effort of having ProdOps and Development working more closely together. As a result, Operations staff do not yet have the in-depth knowledge of the application they might otherwise have.

Operator on-call receives the alert, but doesn’t take immediate action

The operator received the page, but noticed that the values for the queue size were just above the alerting threshold. Considering the recent migration and this being the first time the alert had fired in Production, the operator made the decision to wait, assuming the alert was a spike that would clear itself. You can notice a clear step change in the graph below.

We have many jobs that run on a scheduled basis and these jobs drop a lot of messages in a queue when they start. Those messages usually get consumed relatively quickly, but due to rate limiting by 3rd parties, the processing can slow down. In reality the queue that’s associated with this alert does not exhibit this sort of behavior.

Second Datadog alert fires at 5:37am for direct::deliveryartifactavailableconsumer-perform

After this second alert the Operator knew there must be a problem and began to take action. The operator wasn’t sure how to resolve the problem and said a feeling of panic began to sink in. Troubleshooting from a point of panic can lead to clouded decision making and evaluation. There were no runbooks on this particular alert, so the impact to the end-user was not entirely clear.

The operator decided to restart Sidekiq because the belief was that they were consumers of the queue. The operator had a mental model that resembled Celery, where work was processed by RabbitMQ workers and results were published to a Redis queue for notification. The actual model is the reverse. Workers work off of the Redis queue and publish their results to RabbitMQ. As a result, the Sidekiq workers only publish messages to RabbitMQ but they do not consume messages from RabbitMQ, therefore the Sidekiq restart was fruitless.

The Operator began to troubleshoot using the USE methodology (Utilization, Saturation, Errors) but didn’t find anything alarming. In truth, it turned out that the absence of log messages was the indicator that something was wrong, but the service that should have been logging wasn’t known to the operator. (The Operator assumed it would be Sidekiq workers based on their mental model described above. Sidekiq workers were logging normally)

Operator checks the on-call schedule and notices the Developer on call doesn’t have a phone number listed

The Operator checked the confluence page but didn’t have any contact information or any general information on who to escalate to if the contact listed didn’t respond. This is a solved problem with tools like PagerDuty, where we programmatically handle on-call and escalations. Due to budget concerns though we leverage the confluence page. It could be worthwhile to invest some development effort into automating the on-call process somehow in lieu of adding more users to pager duty. ($29 per user)

Management creates an incident in JIRA and begins assisting in the investigation.

Management began investigating the issue and requested another restart of Sidekiq. The manager assumed that the operator was using Marvin, the chatbot, to restart services. The operator however was unsure of the appropriate name of the services to restart. The help command for the restart service command reads

restart platform service {{ service }} in environment {{ environment }}This was confusing because the operator assumed that {{service}} meant a systemd managed service. We run Sidekiq workers as Systemd services so each worker has a different name, such as int_hub or bi_workers. Because the operator didn’t know the different names, it was much easier to SSH into a box, do the appropriate systemd commands and restart the services.

The disconnect is that {{ service }} is actually an alias that maps to particular application components. One of those aliases is sidekiq, which would have restarted all of the Sidekiq instances including the consumer_daemon, which would have resolved the issue. But because of the confusion surrounding the value of {{ service }}, the operator opted to perform the task manually. In a bit of irony, consumer_daemon is technically not a Sidekiq worker, so it’s also incorrectly classified and could cause further confusion for someone who has a different definition for these workers. The organization needs to work on a standard nomenclature to remove this sort of confusion across disciplines.

Developer identifies that the work queues stopped processing at about 2:05am

When developers began to login, they quickly noticed that the Consumer daemon hadn’t processed anything since 2:05am. This was identified by the absence of log messages in Kibana. This was missed by the Operator for two reasons

- As previously stated, the Operator was unaware that Consumer Daemon was the responsible party for processing this queue, so any log searching was focused on Sidekiq.

- The messages that denoted processing from Consumer Daemon have a much more internal representation. The log entries refer to an internal structure in the code “MappableEntityUpdateConsumer”. But the Operator being unaware of internal structures in the code, would have never correlated that to the behavior being seen. The log message is written for an internal view of the system versus that of an external operator.

Additional Observations

There were some additional observations that came out as part of the general discussion that didn’t map specifically to the timeline but are noteworthy.

activity:historyrecordconsumer is not a real queue

This queue is actually just something of a reporting mechanism. It aggregates the count of all queues and emits that as a metric. When this queue shows a spike in volume, it’s really just an indicator that some other queue is encountering problems. This is an older implementation that may not have value in the current world any longer. It also means that each of our stacked queue graphs are essentially reporting double their actual size. (Since this queue would aggregate the value of all queues, but then also be reported in the stacked graph) We should probably eliminate this queue entirely, but we’ll need to adjust alerting thresholds appropriately with its removal.

Background job exceptions don’t get caught with Airbrake

Airbrake normally catches exceptions and reports them via Slack and email. But background workers (i.e. not Sidekiq) do not report to Airbrake. There have been instances where a background job is throwing exceptions but no action is being taken to remedy.

Fixing the problem vs resolving the incident

Restart the Consumer daemon solved the issue we were having, but there was never any answer as to why every worker node in the fleet suddenly stopped processing from RabbitMQ. The support team was forced to move on to other issues before fully resolving or understanding the nature of the issue.

Action Items

With the observations listed above, we’ve found a few things that will make life easier the next time a similar incident occurs.

- Continue to ensure that our alerting is only alerting when there is a known/definite problem. There’s more value to getting alerts 5 minutes late, but being confident that the alert is valid and actionable. In this case the alerting was correct, but we’ll need to continue to build trust by eliminating noisy alerts.

- Ensure that the On-Call support list has phone numbers listed for each contact. We also need to document the escalation policy for when on-call staff are unavailable. We should also look at automating this, either through expanding PagerDuty or otherwise.

- Marvin chatbot commands need a bit more thorough help page. The suggestion of using a man page like format with a link in the help documentation was suggested.

- Common nomenclature for workers should be evangelized. A simple suggestion is that “workers” accounts for all types of publish/subscribe workers and when we’re talking about a particular subset fo workers we describe the messaging system they interact with. “RabbitMQ Workers” vs “Sidekiq Workers”.

- Support staff need to be afforded the time and energy to study an incident until its cause and prevention are sufficiently understood. We need to augment our processes to allow for this time. This will be a cross-functional effort lead by Prod Ops.

-

I Don’t Understand Immutable Infrastructure

We were at the airport getting ready to go through security. A deep baritone voice shouted, “Everybody must take their shoes off and put them in the bin.” Hearing the instruction I told my son and daughter to take their shoes off and put them in the bin. When we got in line for the X-Ray machine, another man looked at my kids and said “Oh they don’t need to take their shoes off.” My wife and I looked at each other puzzled, “But the man over there said everyone take their shoes off.” “Oh, everyone except children under 12” he responded, as if that was the universal definition of “everybody”. I tell this story to highlight the idea that the words we choose to use matter a great deal when trying to convey an idea, thought or concept. Nowhere is this more true than the world of computing.

Immutable Infrastructure is one of those operational concepts that has been very popular, at least in conference talks. The idea isn’t particularly new, I remember building “golden images” in the 90’s. But there’s no doubt that the web, the rate of change and the tooling to support it has put the core concepts en vogue again. But is what we’re doing really immutable? I feel like it’s not. And while it may be a simple argument over words, we use the benefits of immutability in our arguments without any of the consequences that design choice incurs.

I often hear the argument that configuration management is on its way out, now that we’re ready to usher in an era of “immutable” infrastructure. You don’t push out new configurations, you build new images with the new configuration baked in and replace the existing nodes. How do we define configuration? That answer is simultaneously as concreate and maleable. I define configuration as

The applications, libraries, users, data and settings that are necessary to deliver the intended functionality of an application.

That’s a fairly broad definition, but so is configuration! Configuration management is the process (or absence of process) for managing the components in this list. Therefore if any one of these items is modified, that constitutes not just a change to your configuration, but a changer to your infrastructure as well.

Since we’ve defined configuration, what do we mean by immutability? (Or what do we as an industry mean by it) The traditional definition is

Not subject or susceptible to change or variation in form or quality or nature.

In the industry we boil it down to the basic meaning of “once it’s set, it never changes. A string is often immutable in programming languages. Though we give strings the appearance of mutability, in reality it’s a parlor trick to simplify development. But if you tell a developer that strings are immutable, it conveys a specific set of rules and the consequences for those rules.

What doe these definitions mean in practice? Let’s pretend it’s a normal Tuesday. There’s a 60% chance there’s a new OpenSSL package out and you need to update it. Rolling out a new OpenSSL package by creating a new image for your systems seems like a reasonable methodology. Now there’s a known good configuration of our system that we can replicate like-for-like in the environment. If you’re particularly good at it, getting the change rolled out takes you 30 minutes. (Making the change, pushing it, kicking off the image build process and then replacing, while dialing down traffic) For the rest of us mere mortals, it’s probably closer to a couple of hours. But regardless of time, immutable infrastructure wins!

Now lets pretend we’re in our testing environment. This obviously has a different set of nodes it communicates with vs production, so our configuration is different. We don’t want to maintain to separate images, one for production one for testing because that would rob us of our feeling of certainty about the images being the same. Of course we solve this with service discovery! Now instead of baking this configuration into the application, our nodes can use tools like Consul and Eureka to find the nodes it needs to communicate with. The image remains the same, but the applications configured on the image are neatly updated for reflect their running environment.

But isn’t that a change? And the definition of immutable was that the server doesn’t change. Are we more concerned that OpenSSL stays on the same version than we are about what database server an instance is talking to? I’m sure in the halls of Google, Netflix and LinkedIn, a point release of a library could have catastrophic consequences. But if you asked most of the industry “What frightens you more? Updating to the latest version of OpenSSL or updating worker_threads from 4 to 40?” I imagine most of us would choose the latter with absolutely zero context around what worker_threads is. Let’s wave our magic wand though and say service discovery has also relieved us of this particular concern. Let’s move on to something more basic, like user management.

In testing environments I have widely different access policies than I do for my production systems. I also have a completely different profile of users. In production, operations and a few developers are largely the only people that have access. In testing, development, QA and even product may have a login. How does that get managed? Do I shove that into service discovery as well? I could run LDAP in my environment, but that pushes my issue from “How do I manage users and keys?” to, “How do I manage access policy definitions for the LDAP configuration?”

This is all just to say that I’m incredibly confused about the Immutable Infrastructure conversation. In practice it doesn’t solve a whole host of concerns. Instead it pushes them around into a layer of the system that is often ill suited to the task. Or worse, the idealology simply ignores the failures caused by configuration changes and decides that “Immutable Infrastructure” is actually “Immutable Infrastructure, except for the most dangerous parts of the system”.

This doesn’t even tackle the idea that configuration management is still the best tool for…..wait for it…managing configuration, even if you’re using immutable infrastructure. Docker and Packer both transport us back to the early 90’s in their approach to defining configuration. It be a shame if the death of configuration management was as eminent as some people claim.

So what am I missing? Is there a piece of the puzzle that I’m not aware of? Am I being too pedantic in my definition of things? Or is there always an unexpressed qualifier when we say “immutable”?

Maybe words don’t matter.

-

Our Salt Journey Part 2

Our Salt Journey Part 2

Structuring Our Pillar Data

This is the 2nd part in our Salt Journey story. You can find the previous article here. With our specific goals in mind we decided that designing our pillar data was probably the first step in refactoring our Salt codebase.

Before we start about how we structure Pillar data, we should probably explain what we plan to put in it, as our usage may not line up with other user’s and their expectations. For us, Pillar data is essentially customized configuration data beyond the defaults. Pillar data is less about minion specific data customizations and more about classes of minions getting specific data.

For example, we have a series of grains (which we’ll talk about in a later post) that have classification information. One of the grains set is

class, which identifies the node as being part of development, staging or production. This governs a variety of things we may or may not configure based on the class. If a node is classified asdevelopment, we'll install metrics collections and checks, but the alerting profile for them will be very different than if the node was classified asstagingorproduction.With this in mind, we decided to leverage Pillar Environments in order to create a tiered structure of overrides. We define our pillar’s

top.slsfile in a specific order ofbase,development,stagingand lastlyproductionlike the diagram below.├── base

├── development

│── staging

├── productionIt’s important that we order the files correctly because when the

pillar.get()function executes, it will merge values, but on a conflict the last write wins. We need to ensure that the order the files are read in match the ascending order that we want values to be overridden. In this example, conflicting values in theproductionfolder will override any previously defined values.This design alone however might have unintended consequences. Take for example the below YAML file.

packages:

- tcpdump

- rabbitmq-server

- redisIf this value is set in the

basepillar lookup, then (assuming you've defined base asbase: '*'), then apillar.get('packages')will return the above list. But if you also had the below defined in theproductionenvironment:packages:

- elasticsearchthen your final list would be

packages:

- tcpdump

- rabbitmq-server

- redis

- elasticsearchBecause the

pillar.get()will traverse all of the environments by default. This results in a possible mashup of expected values without care. We protect against this by ensuring that Pillar data is restricted to only nodes that should have access to it. Each pillar environment is guarded by a match syntax based on the grain. Lets say our Pillar data looks like the below:├── base

│ └── apache

│ └── init.sls

├── development

│── staging

│ └── apache

│ └── init.sls

├── production

│ └── apache

│ └── init.slsIf we’re not careful, we can easily have a mashup of values that result in a very confusing server configuration. So in our

top.slsfile we have grain matching that helps prevent this.base:

- apache

-

production:

'G@class:production'

- apacheThis allows us to limit the scope of the nodes that can access the

productionversion of the Apache pillar data and avoids the merge conflict. We repeat this pattern fordevelopmentandstagingas well.What Gets a Pillar File?

Now that we’ve discussed how Pillar data is structured, the question becomes, what actually gets a pillar file? Our previous Pillar structure had quite a number of entries. (I’m not sure that this denotes a bad config however, just an observation) The number of config files was largely driven on how our formulas were defined. All configuration specifics came from pillar data, which meant in order to use any of the formulas, it required some sort of Pillar data before the formula would work.

To correct this we opted to moving default configurations into the formula itself using the standard (I believe?) convention of a

map.jinjafile. If you haven't seen themap.jinjafile before, it's basically a Jinja defined dictionary that allows for setting values based on grains and then ultimately merging that with Pillar data. A common pattern we use is below:A map.jinja for RabbitMQ

{% set rabbitmq = salt['grains.filter_by']({'default': {

},'RedHat': {

'server_environment': 'dev',

'vhost': 'local',

'vm_memory_high_watermark': '0.4',

'tcp_listeners': '5672',

'ssl_listeners': '5673',

'cluster_nodes': '\'rabbit@localhost\'',

'node_type': 'disc',

'verify_method': 'verify_none',

'ssl_versions': ['tlsv1.2', 'tlsv1.1'],

'fail_if_no_peer_cert': 'false',

'version': '3.6.6'

}

})%}With this defined, the formula has everything it needs to execute, even if no Pillar data is defined. The only time you would need to define pillar data is if you wanted to override one of these default properties. This is perfect for formulas you intend to make public, because it makes no assumptions about the user’s pillar environment. Everything the formula needs is self-contained.

Each Pillar file is defined first with the key that matches the formula that’s calling it. So an example Pillar file might be

rabbitmq:

vhost: prod01-server

tcp_listeners: 5673The name spacing is a common approach, but it’s important because it gives you flexibility on where you can define overrides. They can be in their own standalone files or they can be in a pillar definitions for multiple components. For example our home grown applications need to configure multiple pillar data values. Instead of spreading these values out, they’re collapsed with name spacing into a single file.

postgres:

users:

test_app:

ensure: present

password: 'password'

createdb: False

createroles: True

createuser: True

inherit: True

replication: Falsedatabases:

test_app:

owner: 'test_app'

template: 'template0'logging:

- input_type: log

paths:

- /var/log/httpd/access_log

- /var/log/httpd/error_log

- /var/log/httpd/test_app-access.log

- /var/log/httpd/test_app-error.log

- /var/log/httpd/test_app-access.log

- /var/log/httpd/test_app-error.log

document_type: apache

fields: { environment: {{ grains['environment'] }},

application: test_app

}

- input_type: logWe focus on our formulas creating sane defaults specifically for our environment so that we can limit the amount of data that actually needs to go into our Pillar files.

The catch with shoving everything into the

map.jinjafile is that sometimes you have a module that needs a lot of default values. OpenSSH is a perfect example of this. When this happens you're stuck with a few choices:- Create a huge

map.jinjafile to house all these defaults. This can be unruly. - Hardcode defaults into the configuration file template that you’ll be generating, skipping the lookup altogether. This is a decent option if you have a bunch of values that you doubt you’ll ever change. Then you can simply turn them into lookups as you encounter scenarios where you need to deviate from your standard.

- Shove all those defaults into a

basepillar definition and do the lookups there. - Place the massive list of defaults into a

defaults.yamlfile and load that in

We opted for option #3. I think each choice has its pluses and minuses, so you need to figure out what works best for your org. Our choice was largely driven by the OpenSSH formula and its massive number of options being placed in Pillar data. We figured we’d simply follow suit.

This pretty much covers how we’ve structured our Pillar data. Since we started writing this we’ve extended the stack a bit more which we’ll go into in our next post, but for now this is a pretty good snapshot of how we’re handling things.

Gotchas

Of course no system is perfect and we’ve already run into a snag with this approach. Nested lookup overrides is problematic for us. So take for example we have the following in our

base.slsfile:apache:

sites:

cmm:

DocumentRoot: /

RailsEnvironment: developmentand then you decide that you want to override it in a

production.slsPillar file below:apache:

sites:

cmm:

RailsEnvironment: productionWhen you look do a

pillar.get('apache')with a node that has access to the production pillar data, you'd expect to getapache:

sites:

cmm:

DocumentRoot: /

RailsEnvironment: productionbut because Salt won’t handle nested dictionary overrides you instead end up with

apache:

sites:

cmm:

RailsEnvironment: productionwhich of course breaks a bunch of things when you don’t have all the necessary pillar data. Our hack for this has been to have a separate key space for overrides when we have nested properties.

apache_overrides:

sites:

cmm:

RailsEnvironment: productionand then in our Jinja Templates we do the look up like:

{% set apache = salt['pillar.get']('apache') %}

{% set overrides = salt['pillar.get']('apache') %}

{% do apache.update(overrides) %}This allows us to override at any depth and then rely on Python’s dictionary handling to merge the two into a useable Pillar data with all the overrides. In truth we should do this for all look ups just to provide clarity, but because things grew organically we’re definitely not following this practice.

I hope someone out there is finding this useful. We’ll continue to post our wins and losses here, so stay tuned.

- Create a huge

-

Thanks Weighted Decision. Great resources there!

Thanks Weighted Decision. Great resources there!

-

Our Journey with Salt

These are a few of the major pain points that we are trying to address, but obviously we’re going to do it in stages. The very first thing we decided to tackle was formula assignment.

Assigning via hostname has its problems. So we opted to go with leveraging Grains on the node to indicate what type of server it was.

With the role custom grain, we can identify the type of server the node is and based on that, what formulas should be applied to it. So our top.sls file might look something like

'role': 'platform_webserver':

- match: grain

- webserverNothing earth shattering yet, but still a huge upgrade from where we’re at today. The key is getting the grain populated on the server instance prior to the Salt Provisioner bootstrapping the node. We have a few ideas on that, but truth be told, even if we have to manually execute a script to properly populate those fields in the meantime, that’s still a big win for us.

We’ve also decided to add a few more grains to the node to make them useful.

- Environment — This identifies the node as being part of development, staging, production etc. This will be useful to us later when we need to decide what sort of Pillar data to apply to a node.

- Location — This identifies which datacenter the node resides in. It’s easier than trying to infer via an IP address. It also allows us a special case of local for development and testing purposes

With these items decided on, our first task will be to get these grains installed on all of the existing architecture and then re-work our top file. Grains should be the only thing that dictates how a server gets formulas assigned to it. We’re making that explicit rule mainly so we have a consistent mental model of where particular functions or activities are happening and how changes will ripple throughout.

Move Cautiously, But Keep Moving

Whenever you make changes like this to how you work, there’s always going to be questions, doubts or hypotheticals that come up. My advice is to figure out what are the ones you have to deal with, what are the ones you need to think about now and what you can punt on till later. Follow the principle of YAGNI as much as possible. Tackle problems as they become problems, but pay no attention to the hypotheticals.

Another point is to be clear about the trade-offs. No system is perfect. You’ll be constantly making design choices that make one thing easer, but another thing harder. Make that choice with eyes wide open, document it and move on.

It’s so easy to get paralyzed at the whiteboard as you come up with a million and one reasons why something won’t work. Don’t give in to that pessimistic impulse. Keep driving forward, keep making decisions and tradeoffs. Keep making progress.

We’ll be back after we decide what in the hell we’re going to do with Pillar data.

-

Being a Fan

Being a Fan

It was November 26th 1989, my first live football game. The Atlanta Falcons were taking on the New York Jets at Giant’s stadium. I was 11 years old. A friend of my father’s had a son that played for the Falcons, Jamie Dukes. They invited us down for the game since it was relatively close to my hometown. Before the game we all had breakfast together. Jamie invited a teammate of his, a rookie cornerback named Deion Sanders, to join us. The game was forgettable. The Falcons got pounded, which was par for the course that year. But it didn’t matter, I was hooked.

For the non-sports fan, the level of emotional investment fans have may seem like an elaborate ponzi scheme. Fans pour money into t-shirts, jerseys, hats, tickets etc. When the dream is realized, when your team lifts that Lombardi trophy and are declared champions, the fan gets……nothing. No endorsement deals. No free trophy replica. No personal phone call from the players. Nothing. We’re not blind to the arrangement. We enter it willingly. To the uninitiated it’s the sort of hero-worshiping you’re supposed to shed when you’re 11 years old. Ironically this is when initiation is most successful.

Fandom is tribalism. Tribalism is at the epicenter of the human condition. We dress it up with constructs as sweeping as culture and language and as mundane as logos and greek letters. We strive to belong to something and we reflexively otherize people not of our tribe. Look at race, religion or politics.

But that’s the beauty of sports. The otherization floats on an undercurrent of respect and admiration. That otherization fuels the gameday fire, but extinguishes itself when a player lays motionless on the field. That otherization stirs the passion that leads to pre-game trash talk, but ends in a handshake in the middle of the field. That otherization causes friendly jabs from the guy in a Green Bay jersey in front of you at the store, but ends in a “good luck today” as you part ways.

In today’s political and social climate, sports are not just an escape, but a blueprint for how to handle our most human of urges. Otherization in sports has rules, but those rules end in respect for each other and respect for the game. I read the lovefest between these two teams and think how much it differs from our political discourse. If the rules of behavior for politicans changed, so would the rules for its fans.

Fandom is forged in the furnace of tribalism. As time passes it hardens. Eventually, it won’t bend, it won’t break. A bad season may dull it, but a good season will sharpen it. You don’t choose to become a fan. Through life and circumstance, it just happens. By the time you realize you’re sad on Mondays after a loss, it’s too late. You’re hooked.

Best of luck to the Patriots. Even more luck to the Falcons. Win or lose, I’ll be with the tribe next year…and the year after that…and the year after. I don’t have a choice. I’m a fan. #RiseUp

-

The Myth of the Working Manager

The Myth of the Working Manager

The tech world is full of job descriptions that describe the role of the workingmanager. The title itself is a condescension, as if management alone doesn’t rise to the challenge of being challenging.

I was discussing DHH’s post on Moonlighting Managers with a colleague when it occurred to me that many people have a fundamental misunderstanding of what a manager should do. We’ve polluted the workforce with so many bad managers that their toxic effects on teams hovers like an inescapable fog. The exception has become the rule.

When we talk about management, what we’re often describing are more supervisory tasks than actual management. Coordinating time-off, clearing blockers and scheduling one-on-ones is probably the bare minimum necessary to consider yourself management. There’s an exhaustive list of other activities that management should be responsible for, but because most of us have spent decades being lead in a haze of incompetency, our careers have been devoid of these actions. That void eventually gives birth to our expectations and what follows is our collective standards being silently lowered.

Management goes beyond just people management. A manager is seldom assigned to people or a team. A manager is assigned to some sort of business function. The people come as a by-product of that function. This doesn’t lessen the importance of the staff, but it highlights an additional scope of responsibility for management, the business function. You’re usually promoted to Manager of Production Operations not Manager of Alpha Team. Even when the latter is true, the former is almost always implied by virtue of Alpha Team’s alignment in the organization.

As the manager of Production Operations, I’m just as responsible for the professional development of my team as I am for the stability of the platform. Stability goes beyond simply having two of everything. Stability requires a strategy and vision on how you build tools, from development environments to production. These strategies don’t come into the world fully formed. They require collaboration, a bit of persuasion, measurement, analysis and most notably, time. It’s the OODA loop on a larger time scale.

Sadly, we use reductive terms like measurement and analysis which obfuscates the complexity buried within them. How do you measure a given task? What measurement makes something a success or failure? How do you acquire those measurements without being overly meddlesome with things like tickets and classifications. (Hint: You have to sell the vision to your team, which also takes time) When managers cheat themselves of the time needed to meet these goals, they’re technically in dereliction of their responsibilities. The combination of a lack of time with a lack of training leads to a cocktail of failure.

This little exercise only accounts for the standard vanilla items in the job description. It doesn’t include projects, incidents, prioritization etc. Now somewhere inside of this barrage of responsibility, you’re also supposed to spend time as an engineer, creating, reviewing and approving code among other things. Ask most working managers and they’ll tell you that the split between management and contributor is not what was advertised. They also probably feel that they half-ass both halves of their job, which is always a pleasant feeling.

I know that there are exceptions to this rule. But those exceptions are truly exceptional people. To hold them up as the standard is like my wife saying Why can’t you be more like Usher? Lets not suggest only hiring these exceptional people unless you work for a Facebook or Google or an Uber. They have the resources and the name recognition to hold out for that unicorn. If you’re a startup in the mid-west trying to become the Uber of knitting supplies, then chances are your list of qualified candidates looks different.

The idea of a working manager is a bit redundant, like an engineering engineer. Management is a full-time job. While the efficacy of the role continues to dwindle, we should not compound the situation by also dwindling our expectations of managers, both as people and as organizations. Truth be told the working manager is often a creative crutch as organizations grapple with the need to offer career advancement for technical people who detest the job of management.

But someone has to evaluate the quality of our work as engineers and by extension, as employees. Since we know the pool of competent managers is small, we settle for the next best thing. An awesome engineer but an abysmal manager serving as an adequate supervisor.

The fix is simple.

- Recognize that management is a different skill set. Being a great engineer doesn’t make you a great manager.

- Training, training, training for those entering management for the first time. Mandatory training, not just offering courses that you know nobody actually has time to take.

- Time. People need time in order to manage effectively. If you’re promoting engineers to management and time is tight, they’ll always gravitate towards the thing they’re strongest at. (Coding)

- Empower management. Make the responsibilities, the tools and the expectations match the role.

Strong management, makes strong organizations. It’s worth the effort to make sure management succeeds.

-

When You Think You’re a Fraud

When You Think You’re a Fraud

Imposter Syndrome is a lot like alcoholism or gout. It comes in waves, but even when you’re not having an episode, it sits there dormant, waiting for the right mix of circumstances to trigger a flare up.

Hi, my name is Jeff and I have Imposter Syndrome. I’ve said this out loud a number of times and it always makes me feel better to know that others share my somewhat irrational fears. It’s one of the most ironic set of emotions I think I’ve ever experienced. The feelings are a downward spiral where you even question your ability to self-diagnose. (Who knows? Maybe I just suck at my job )

I can’t help but compare myself to others in the field, but I’m pretty comfortable recognizing someone else’s skill level, even when it’s better than my own. My triggers are more about what others expect my knowledge level to be at, regardless of how absurd those expectations are. For example, I’ve never actually worked with MongoDB. Sure, I’ve read about it, I’m aware of its capabilities and maybe even a few of its hurdles. But I’m far from an expert on it, despite its popularity. This isn’t a failing of my own, but merely a happen-stance of my career path. I just never had an opportunity to use or implement it.

For those of us with my strand of imposter syndrome, this opportunity doesn’t always trigger the excitement of learning something new, but the colossal self-loathing for not having already known it. Being asked a question I don’t have an answer to is my recurring stress dream. But this feeling isn’t entirely internal. It’s also environmental.

Google did a study recently that said the greatest indicator for high performing teams is being nice. That’s the sort of touchy, feely response that engineers tend to shy away from, but it’s exactly the sort of thing that eases imposter syndrome. Feeling comfortable enough to acknowledge your ignorance is worth its weight in gold. There’s no compensation plan in the world that can compete with a team you trust. There’s no compensation plan in the world that can make up for a team you don’t. When you fear not knowing or asking for help out of embarrassment, you know things have gone bad. That’s not always on you.

The needs of an employee and the working environment aren’t always a match. The same way some alcoholics can function at alcohol related functions and others can’t. There’s no right or wrong, you just need to be aware of the environment you need and try to find it.

Imposter syndrome has some other effects on me. I tend to combat it by throwing myself into my work. If I read one more blog post, launch one more app or go to one more meetup, then I’ll be cured. At least until the next time something new (or new to me) pops up. While I love reading about technology, there’s an opportunity cost that tends to get really expensive. (Family time, hobby time or just plain old down time)

If you’re a lead in your org, you can help folks like me with a few simple things

- Be vulnerable. Things are easier when you’re not alone

- Make failure less risky. It might be through tools, coaching, automation etc. But make failure as safe as you can.

- When challenging ideas propose problems to solve instead of problems that halt. “It’s not stateless” sounds a lot worse than “We need to figure out if we can make it stateless”

Writing this post has been difficult, mainly because 1) I don’t have any answers and 2) It’s hard not to feel like I’m just whining. But I thought I’d put it out there to jump start a conversation amongst people I know. I’ve jokingly suggested an Imposter Syndrome support group, but the more I think about it, the more it sounds like a good idea.

-

People, Process, Tools, in that Order

People, Process, Tools, in that Order

Imagine you’re at a car dealership. You see a brand new, state of the art electric car on sale for a killer price. It’s an efficiency car that seats two, but it comes with a free bike rack and a roof attachment for transporting larger items if needed.

You start thinking of all the money you’d save on gas. You could spend more time riding the bike trails with that handy rack on the back. And the car is still an option for your hiking trips with that sweet ass roof rack. You’re sold. You buy it at a killer deal. As you drive your new toy home, you pull into the driveway and spontaneously realize a few things.

- You don’t hike

- You live close enough to bike to the trail without needing the car

- You don’t have an electrical outlet anywhere near the driveway

- You have no way of fitting your wife and your 3 kids into this awesome 2 seater.

This might sound like the beginning of a sitcom episode, where the car buyer vehemently defends their choice for 22 minutes before ultimately returning the car. But this is also real life in countless technology organizations. In most companies, the experiment lasts a lot longer than an episode of Seinfeld.

In technology circles, we tend to solve our problems in a backwards fashion. We pick the technology, retrofit our process to fit with that technology, then we get people onboard with our newfound wizardry. But that’s exactly why so many technology projects fail to deliver on the business value they’re purported to provide. We simply don’t know what problem we’re solving for.

The technology first model is broken. I think most of us would agree on that, despite how difficult it is to avoid. A better order would be

People -> Process -> Tools

is the way we should be thinking about how we apply technology to solve business problems, as opposed to technology for the sake of itself.

People

Decisions in a vacuum are flawed. Decisions by committee are non-existent. Success is in the middle, but It’s a delicate balance to maintain. The goal is to identify who the key stakeholders are for any given problem that’s being solved. Get the team engaged early and make sure that everyone is in agreement on the problem that’s being solved. This eliminates a lot of unnecessary toil on items that ultimately don’t matter. Once the team is onboard you can move on to…

Process

Back in the old days, companies would design their own processes instead of conforming to the needs of a tool. If you define your process up front, you have assurances that you’ve addressed your business need, as well as identified what is a “must have” in your tool choice. If you’ve got multiple requirements, it might be worthwhile to go through a weighting exercise so you can codify exactly which requirements have priority. (Requirements are not equal)

Tools

Armed with the right people and the process you need to conform to, choosing a tool becomes a lot easier. You can probably eliminate entire classes of solutions in some instances. Your weighted requirements is also a voice in the process. Yes Docker is awesome, but if you can meet your needs using VMs and existing config management tools, that sub-second boot time suddenly truffle salt. (Nice to have, but expensive as HELL)

Following this order of operations isn’t guaranteed to solve all your problems, but it will definitely eliminate a lot of them. Before you decide to Dockerize your MySQL instance, take a breath and ask yourself, “Why am I starting with a soution?”

-

Metrics Driven Development?

Metrics Driven Development?

At the Minneapolis DevOps Days during the open space portion of the program, Markus Silpala proposed the idea of Metrics Driven Development. The hope was that it could bring the same sort of value to monitoring and alerting that TDD brought to the testing world.

Admittedly I was a bit skeptical of the idea, but was intrigued enough to attend the space and holy shit-balls am I glad I did.

The premise is simple. A series of automated tests that could confirm that a service was emitting the right kind of metrics. The more I thought about it, the more I considered its power.

Imagine a world where Operations has a codified series of requirements (tests) on what your application should be providing feedback on. With a completely new project you could run the test harness and see results like

expected application to emit http.status.200 metric

expected application to emit application.health.ok metric

expected application to emit http.response.time metric

These are fairly straight forward examples, but they could quickly become more elaborate with a little codification by the organization.

Potential benefits:

- Operations could own the creation of the tests, serving as an easy way to tell developers the types of metrics that should be reported.

- It helps to codify how metrics should be named. A change in metric names (or a typo in the code) would be caught.

Potential hurdles:

- The team will need to provide some sort of bootstrap environment for the testing. Perhaps a docker container for hosting a local Graphite instance for the SUT.

- You’ll need a naming convention/standard of some sort to be able to identify business level metrics that don’t fall under standard naming conventions.

I’m sure there are more, but I’m just trying to write down these thoughts while they’re relatively fresh in my mind. I’m thinking the test harness would be an extension of existing framework DSLs. For an RSpec type example:

describe “http call”

context “valid response”

subject { metrics.retrieve_all }before(:each)

get :index {}end

it { expect(subject).to have_metric(http.status.200)}it { expect(subject).to have_metric(http.response.time)}end

end

This is just a rough sketch using RSpec, but I think it gets the idea across. You’d also have to configure the test to launch the docker container, but I left that part out of the example.

Leaving the open space I was extremely curious about this as an idea and an approach, so I thought I’d ask the world. Does this make sense? Has Markus landed on something? What are the HUGE hurdles I’m missing. And most importantly, do people see potential value in this? Shout it out in the comments!