Decision Rights — Communicating How Choices Get Made

Decision Rights — Communicating How Choices Get Made

Advice for leaders

Companies seldom have issues generating ideas and paths forward on problems. In fact, you almost get too many ideas to be able to sift through, evaluate and ultimately implement. But a bigger problem teams have isn’t generating options, but choosing which option to go forward with. (The next issue is aligning resources, but that’s a future topic) The issue of deciding on a course of action is further exacerbated when we have groups of people working on a problem with no clear idea of who the decision owner is.

At Basis Technologies we follow many of the principles and practices of the Conscious Leadership Group. The trainings we’ve had have been invaluable for me as a leader, but one of the best takeaways so far has been the concept of Decision Rights. In a nut-shell, decision rights are a clear definition of who will make a decision for any given situation. I’ve been using decision rights a lot more now that my team has grown and we’re spread out across three countries. The benefits of easy informal communication have begun to disappear as my organization grows and I needed something more formal to ensure the team is on the same page.

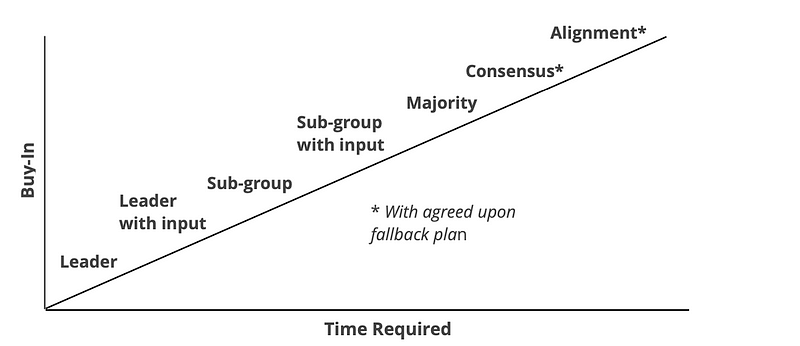

There are a total of 7 decision rights with each change in decision rights also increasing the amount of time required to reach the decision and the amount of buy-in received from the group. This will make a bit more sense as I walk through the 7 decision rights really quickly.

Decision Rights

- Leader — We are all pretty familiar with the leader decision right. It’s just like it sounds, the leader of the group (assuming there’s one clearly defined) will make the decision on his/her own.

- Leader with Input — The leader will gather input from others before making their decision. The leader usually will be responsible for soliciting the information they feel is necessary for input to their thought process.

- Subgroup — A small team of people are put together to make a decision. The team is typically made up of Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) that drive all aspects of the decision making process.

- Subgroup with input — A subgroup with input means that the subgroup still decides, but solicits information from outside the group as well, before making a decision.

- Majority Vote — A group discussion of some sort ensues, followed by a voting period. Everyone should have an opportunity to voice their thoughts and concerns prior to voting. Think of it like an election, where each candidate (or view point in our scenario) has an opportunity to discuss their feelings on the situation. After that period has finished, voting occurs and majority wins. The leader of the group or organization will decide what type of majority is needed, whether it be just a simple majority, two thirds majority etc.

- Consensus — Consensus happens when there is nobody that is opposed to the decision being made. It doesn’t mean that they can’t have doubts or reservations, but they’re not actively against it. This is your classic dinner planning scenario. You’re not against steak, even though you’d rather have pasta, but the rest of the group wants steak and you can get behind it. But just like your dinner plans, consensus decisions can be difficult to reach, so it’s wise to have a fall back decision right in the event you can’t reach consensus. Any of the previously mentioned decision rights can work, but I typically fall back to Leader with Input.

- Alignment — Alignment is when every one is in full support of the decision being made. There is no dissent. This is the hardest of all the decision rights to meet. If you can’t get alignment on dinner, getting alignment on transformational change can be very hard. Like the consensus decision right, it’s important to have a fall back decision right in case alignment cannot be reached.

With these 7 decision rights laid out, we can talk about buy-in vs time. Depending on the urgency of the decision that has to be made, some decision rights might seem more obvious than others.

In the above image you can see the various decision rights plotted on a graph, with the axis being buy-in and time. These are typically the two constraints that we’re working with when it comes to decision making. Buy-in can be incredibly important for large transformational change, but time may be of the essence when we’re trying to make a decision about something this quarter. There is no right or wrong answer for choosing a decision right. It all boils down to the situation at-hand and the constraints that you’re working under. If you’ve got more time, achieving more buy-in makes sense which can lead you to decision rights like Alignment or Consensus. Any decision typically benefits from a larger buy-in from the team. The problem is not every decision has the time necessary to get there, which makes some of the other decision rights attractive and appropriate for the situation at hand.

Communicating Decision Rights

I don’t use formal communication for every decision right in our team. I typically reserve it for broad impacting decisions that I know many people will have feelings about. I also don’t discuss decision rights when it’s Leader decides, because then it’s usually quite clear. It’s a terrible feeling thinking you’ve got input on a decision when you don’t. If I come to the team with a decision already made, I make that clear with the delivery of the decision. Again, this is a rare occurrence, but it does happen.

When I am communicating decision rights, it’s usually in this old, antiquated form of communication called a “Meeting Agenda”. Some of you may remember those from back in the day when it was important to know what you were going to be spending 1.5 hours of your life on. In the meeting agenda I try to lay out a few things.

- What the decision to be made is

- The timeframe allotted to make the decision (often just the length of the meeting)

- What the decision right is

- What the fallback decision right is (if applicable)

- Any tools being used to generate decision options (Brainstorming, Pros vs Cons, 6 Hats, etc)

With these points in hand, everyone clearly understands their part in the decision-making process and how decisions gets made. Even if people don’t agree with the final decision, the process to which it came into being is well-understood and transparent. The agenda doesn’t even have to be super-exhaustive. Here’s an example agenda I’ve used in the past.

Lets get together and discuss namespaces moving forward.

Problem: We need to decide if we’re going to have a single namespace per environment or if namespaces will be broken down by application. Single namespaces are advantageous in test environments, but can become unruly in production. Multiple name spaces can complicate environment management and will force specific patterns of referencing apps in pods, since you’ll have to use the FQDN. None of these are hard, but we need a specific choice.

Meeting Outcome: Decide on single name space or multiple name spaces. Decision Model: Group Consensus with a fall back of Leader Decides with input from staff, if we can’t come to a consensus.

Pros/Cons Idea Boardz

It’s just enough information to get everyone on the same page without taking tons of times crafting time blocks that probably won’t be honored anyways. (Although if you’ve got the time for a more detailed agenda it’s totally worth it. I’m just saying that there’s still value in a brief agenda if the alternative is no agenda at all)

Wrap-up

Decision rights can be a tricky thing once you’ve moved beyond the leader decides tier. Making sure people involved and impacted by the decision are aware of how decisions are made can lead to greater buy-in even after the decision has been made. Communicating these decision rights can be a huge boost to involvement and productivity. It also forces you to make rationale decisions about the two constraints of every decision, time and buy-in. The more time you have the more you can invest in getting larger buy-in. But if time is short, you may have to make due with less buy-in so that you can get the ball rolling on whatever decision you make. These pressures exist whether you acknowledge them or not so its better to go into the situation eyes-wide-open. It can even help you communicate why such a narrow buy-in was chosen. Not every decision has a time-horizon that can afford alignment or even consensus. Does this mean some decisions are sub-optimal? Of course. But a sub-optimal decision is way better than no decision at-all.

If you’d like to further dive-in or see a visual representation of Decision Rights, I’ve linked a video below and I encourage you to checkout the Conscious Leadership group.