-

Hunting Warhead - ★★★★★

Hunting Warhead is a podcast about some very difficult subject matter. The podcast follows the hunt for the moderator of one of the biggest child pornography/abuse websites on the dark web. The story explores the underbelly of the web and the horrific subculture. I was hesitant to listen to it at first, but the host did as well as any navigating the topic, avoiding unnecessary graphic detail.

It’s a difficult topic, but as a society, we can’t bury our heads in the sand about it. It’s more prevalent than we think.

-

Decided to break the drive back to Chicago up. Grabbed a hotel and relaxing, watching Blue Eyed Samurai. Will finish up the drive in the morning.

-

It’s done. Mom, Grandma, Granny, Auntie El, Goosey Maye. So many names, titles of affection and love. You’ll be missed. Your family celebrated you hard today.

-

I recorded a conversation with my Mom a couple years ago where we discussed family history and events. Starting to go through it now and make smaller clips of it. Here’s the first one talking about the origins of our family reunion.

-

My Frustrations with D&D

Screenrant published an article about the departure of two key figures on the D&D design team, Jeremy Crawford and Chris Perkins. They’ve been helming the creative side of the franchise for over a decade and have overseen the development of 5E and what I guess we’re calling 5.5E.

The latest versions of D&D have brought in an avalanche of new players. (It might also have to do with the rising popularity of actual-play streams as well) More people playing TTRPGs is good for the hobby, no matter their entry vehicle. But I can’t say that I’m happy with the overall trajectory of D&D specifically. I’ve been trying to put my finger on precisely what bothers me about the direction of the franchise.

At the heart of my issue is the ever-increasing power levels of characters and the lengths a DM has to go through to challenge players. That sounds like a simple problem as a DM since you have control over the force you apply to the party. But it can get tricky very quickly.

Encounter levels

For starters, I never want to create an overwhelming encounter. That’s as much fun as having players annihilate their opposition in every battle. I want there to be an opportunity for the players to win, but with heavy costs. That balance seems very difficult to strike in 5E. (I’m including 5.5E in my references to 5E. I hate writing 5.5E) Either you’re coming on too strong, and you wipe the party or find some unsatisfying excuse to keep them from dying, or the encounter is an exercise in hit-point bookkeeping. The challenge rating system is broken, but many people in the community have devised ways to try and correct it. But even with those tips, it’s hard to nail down consistently.

Another wrinkle for balanced encounters are the different power levels of characters when playing with min/maxers or broken builds of characters. (The Monk class is ripe for exploitation) Now, you have a character that requires more of a challenge, sandwiched amongst squishier characters who can’t handle the increased intensity of the confrontation. Do you make it challenging for one at the expense of the others? Or do you make the encounter level with the rest of the party and let the min/maxer have a field day? The other option is limiting people’s ability to min/max, but now you’re applying a subjective set of rules and possibly preventing a player from playing the character they want. You have to pick one thing to optimize for and go for it. It’s all about trade-offs. There are no free lunches here.

Character Death

This extends my encounter problem, but killing characters is hard. I’m not the DM who wants to murder characters regularly. I think character death should be rare but still a possibility. In 5E, it’s arduous to have a character die as part of the natural flow of a battle. Sure, I can kill a character intentionally, but that doesn’t seem fun or fair. The specter of death always increases the tension and the stakes of a battle. (Yes, I know, there are other ways to create that as well) But it often doesn’t feel that death is an actual risk during an encounter.

An aside on this. If you look at the roots of D&D, you don’t want to go back to that, where characters were a collection of stats with a name. Character death was frequent and a non-event. It wasn’t until The Hickman Revolution that we started to get stories with overarching plots and player character motivations taken into account. But you can’t have a cohesive narrative if the characters die every third or fourth session. You’re stuck. You’ve got to find a middle ground of some sort. There are no free lunches.

Simulation vs Abstraction

The D&D game has become (again) highly tactical. The game transforms as you transition from roleplaying to combat in what feels like a different game. (This feeling has steadily increased since 3rd edition and the move away from theater of the mind combat.) I’ve become keenly aware that D&D is not a simulation of the real world in any facet.

This isn’t a knock on the system at all. It’s a deliberate design choice you either like or don’t. But I’ve spent countless hours at tables debating the “real world” impact of spells like Darkness where you’re effectively blind. You’d think you couldn’t attack a target you can’t see. But in the game, you can attack but with disadvantage. Some people take issue with that. Let’s say they’re hiding from the blinded attacker or they’re not making any sound. “How can they attack me? They’re blind!” The game rules don’t handle that real-world logic leap. Because it’s not a simulation. Realism gives way to the mechanics of the system. You can house-rule it, but then you might find yourself in an endless loop of exceptions and “whatabout” type of arguments. Narrative-based games like those inspired by the Powered by the Apocalypse system have an advantage here but come with their own problems. There are no free lunches.

Wilderness Adventuring Takes a Back Seat

Exploring the wilderness has taken a back seat in 5E. I started to put together a hex crawl adventure for my table and quickly realized how 5E has dismantled a lot of the challenges of surviving in the wilderness. An argument can be made that players don’t find those types of survival adventures enjoyable, which is fair. But I miss that aspect of the game. Getting to the location was just as dangerous as exploring it. It created a need for a diverse set of skills and abilities. Now Create food and water generates 45 pounds of food. The Natural Explorer class feature eliminates a lot of the troubles of exploration. And these are just items in the Players Handbook! Again, wilderness exploration might not be your thing, so I recognize that I could be in the minority here.

What to do?

All this rambling is to say that some of the core aspects I remember of the game growing up have slowly changed to a point where D&D isn’t the first place I want to go regarding TTRPGs. The franchise still has a special place in my heart and should continue on its current path because it’s bringing a massive new audience to the hobby. And when new people enter the hobby, we all win. But it might be time for me to get off the D&D train and start exploring other systems. I’ve already mentioned the PbtA system of games. A few others that I’m interested in.

- Blades in the Dark

- Shadowdark

- Scum and Villainy

- Dungeon Crawl Classics (Although this might have too much lethality)

There are a ton of options out there. I’m looking forward to exploring them!

-

Looong drive to Georgia. Binged a podcast called Scamanda. Woman faked a Cancer diagnosis and scammed her followers and her church out of thousands in donations. Wild. Definitely worth listening to, but it it’s one of those podcasts that didn’t need to be that long.

-

Rhythms of Life

There are rhythms to life that are both natural and unsettling at the same time. I’m currently experiencing two at the same time. The loss of a parent, and entering the stage of life with no living parents.

It’s bizarre that these events feel tragic and unfair. When I examine it even casually, it’s the natural order of things. Parents should never have to bury their children so naturally the reverse must be true. But experiencing it gives a feeling of your roots being razed.

The feelings become more complex when your parent(s) lived somewhere that you strongly identify with them. How does that place fit into your life now that there’s a large piece of the puzzle missing? Will it ever feel the same?

I’m preparing for the long, solitary drive down to Georgia to help with the funeral arrangements. I feel an odd sense of relief to be making this drive alone and giving myself an opportunity to process things internally. A chance for thought and reflection unrestrained by the need to be OK.

I wish this post had more clear goals. You’re being subjected to a semi-stream of consciousness as I process my grief through words. Why I’m processing it publicly is beyond me. But it feels right.

-

Watching your parents get old is never easy. Glad I got to see Mom recently. Her health isn’t great and I know our days are numbered. It’s been…..hard.

-

The Girlfriends, a True Crime Podcast

Like most people, I’ve been enjoying true crime podcasts. They can be hit or miss depending on the crime and the host. Since Serial launched, there’s been a deluge of amateur podcasters doing these shows. Hit or miss. This one is a hit IMO.

-

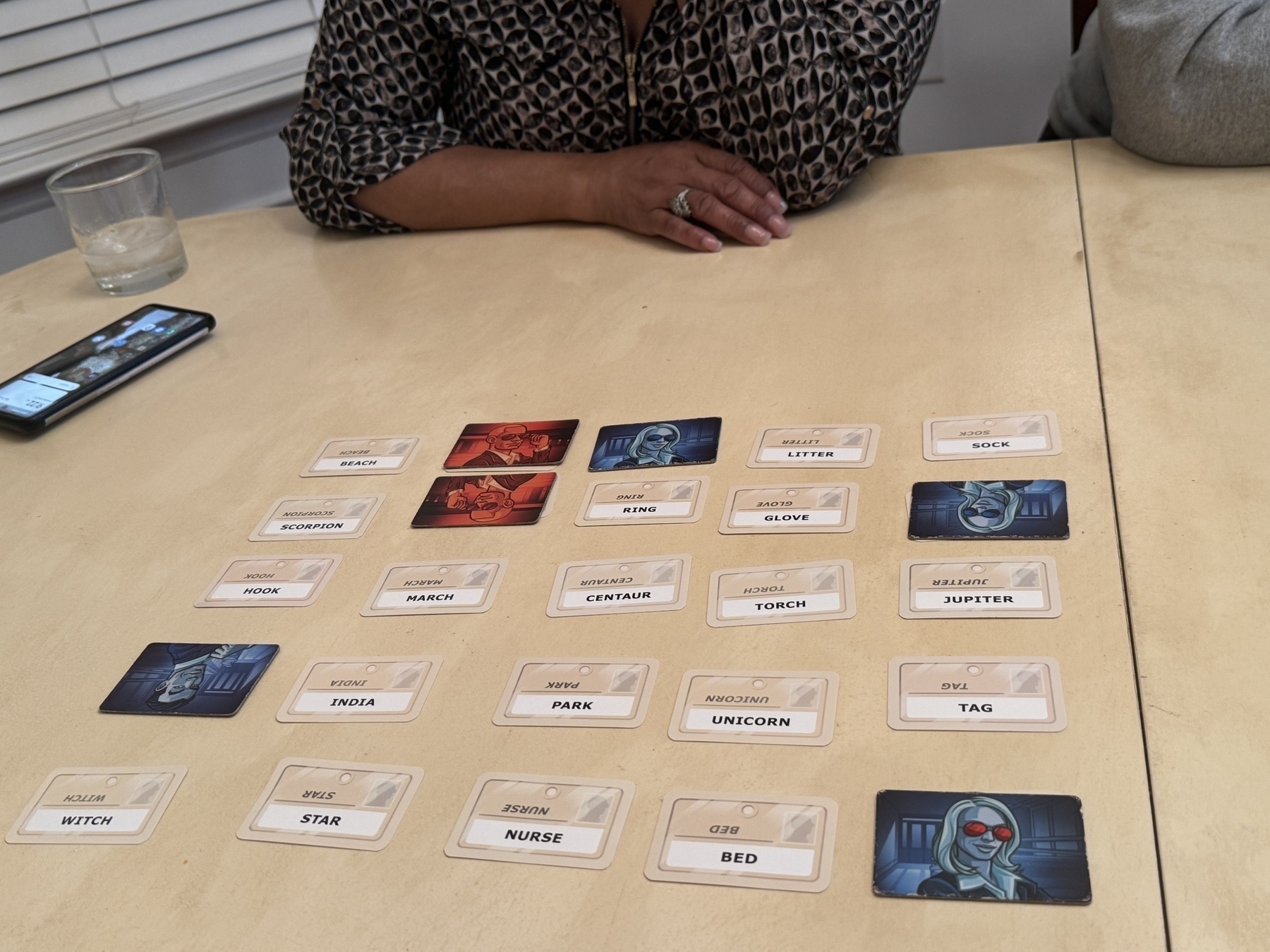

A friendly game of Codenames going on with family. Visiting my mother in Georgia. Had to drive because I’m still not cleared to fly. But she’s been sick, so I had to get down here. Cherish your loved ones.

-

In tech we seem to redefine terms that are difficult to do right. Continuous Integration had a very specific definition. Now it just means you run Jenkins. Microservices were defined by tight size and tight boundaries. Now it’s just SOA. GitOps is devolving to just having your config in Git.

-

Saying "No" is Merciful

Many of us have issues saying “no.” It’s a funny hangup when you think about it. But we all bring our baggage when it comes to using the word. I’m a people pleaser by nature, so telling someone “no” puts me in the uncomfortable position of being the seed of disappointment for someone.

In a work context, it’s essential to recognize that “no” is merciful, specifically the explicit “no.” There are two types of no, the eventual and the explicit. The explicit “no” is the one we’re all familiar with.

“Can you run Friday’s meeting?”

“No. I can’t.”

That’s the explicit “no” that most of us dread using. Then there’s the eventual “no.”

“Can your team develop that feature?”

“Sure. I’ll add it to the backlog, and we’ll prioritize it when we can.”

That one is the eventual “no.” It relieves you of the social burden of disappointing someone but also conveys a false hope for people who can’t read between the lines. And that’s where things become cruel.

With an explicit “no,” people will initially feel some discomfort. It’s only natural to feel that way. However, everyone eventually gets over it and can begin planning with this new reality in mind. The eventual “no” robs the requester of any agency to make alternative plans. You’ve committed, however soft, to deliver eventually. The backlog seems like an appropriate place for these requests; it becomes apparent when something isn’t going to be done. If you haven’t prioritized it in 4 weeks, chances are you won’t prioritize it in 4 months or 4 quarters. Meanwhile, someone is sitting on the other end of that ticket, not taking action on alternative options because of the false hope you’ve given them. Once you both face reality, valuable time has been wasted, goodwill burned, and that seed of disappointment you were avoiding has already sprung into a full-grown oak tree.

So what’s the value of the eventual “no?” As mentioned previously, it’s a defense mechanism against short-term pain or discomfort. It’s easier to say no and push off the pain of disappointment until later. We might even convince ourselves that we’re going to fulfill the request. You’d be surprised how easy it is, in the moment, to trick yourself into thinking you have capacity you don’t have.

How do you avoid using the eventual “no?” The easiest trick I’ve found is always to give a date. If you can’t provide a date, you’re probably not serious about meeting the request.

- Can you commit to it in the next two weeks?

- If you can commit to it in the next two weeks, does it require you to push something else out? If so, identify that thing immediately before committing. If you can’t determine what to not do, you can’t commit.

- If you can’t commit in the next two weeks, can you commit within this quarter or next? If you can’t commit to it in that time frame, consider using the explicit no.

Now, no is not forever. Someone can always come back and ask the question again; perhaps the situation has changed. Also, you can always consider going beyond just the next quarter, but in my experience, quarterly planning goes something like this. (Assume it’s the start of the year)

- The first quarter plan is solid

- The second has the bones of a plan but is still a little handwavy.

- The third quarter is 100% handwavy.

- The fourth quarter should be treated with the same certainty as astrology and economic forecasting

If you want to hedge your bets, you can always ask the person to check back in after a certain amount of time has passed. You haven’t committed and are allowed to reconsider the request soon. But you’ll have to run through the whole exercise again to see if you can commit. While I don’t love this option because it’s just an extension of the eventual “no,” it’s sometimes necessary, depending on the request.

Make no mistake: The eventual “no” is a cancer in most organizations. It eventually metastasizes and begins to impact work well beyond the scope of the initial request. Be merciful and use the explicit “no” more often.

-

Finished reading: Notes on the Synthesis of Form by Christopher Alexander 📚

I learned about Christopher Alexander from a video by Ryan Singer. I have no idea how I stumbled upon Ryan’s video though so the whole experience felt surreal. Either way, I was fortunate that the local library had a copy so I said what the hell and gave it a read.

I’m not a designer per se but I think most of us have some design responsibilities in our roles. This book starts strong, using abstract terminology to describe the problem space of design. Even though Alexander may be talking about architecture, mapping his points to your field was straight forward. But as you get deeper into the book the more esoteric it becomes.

This might be due to my own deficiencies but I got lost once the book turned to math proofs on variables of design requirements in a problem space to evaluate the fit of a solution to a problem. Luckily the book is fairly short at about 140 pages, so tail end confusion aside, it was worth the read. It gave language to the design problems and new ways to think about how we identify and evaluate potential solutions. (I believe this is what Alexander calls a “pattern language”, which he has another book about)

This is just one of a few books by Alexander and while I don’t do enough design work to continue diving into his catalog, those who do design daily might find it useful. Ryan’s video is a primer into Alexander’s work but even that veers into the swamp of the abstract.

-

My Conversion to a ChatGPT Promoter

My Conversion to a ChatGPT Promoter

I’ve been lukewarm on ChatGPT and generative AI. I saw the potential but predicted (erroneously) that we were still far removed from it being generally useful and reliable. Those ideas were formed through experience, incorrect comparisons and a lack of imagination on my part.

I wanted to write this post to give context to my skepticism and provide examples (with prompts) on generative AI’s usefulness. When I read articles on the web I see these very vague stories and trivial use cases that don’t inspire me. (Except meeting note transcribers, which in my experience have been universally amazing) I hope someone finds this useful and inspiring.

A little history

I’d used MidJourney, an image generation tool, for a bit to create images for my D&D game. MidJourney generally performed well if I kept the prompts basic. But the tool (at the time) had some odd side effects. For example, it was horrible at generating images of hands, so anything that required hands, like a wizard casting a spell, was a hot mess. It also didn’t do a good job of interpreting my intent and translating that into a sensible image. Minutes before writing this blog post I used the following prompt with MidJourney.

a centaur in the forrest hunting a deer with a bow and arrow

It generated the image below

Not exactly instilling confidence in me. This helped to shape my perception of what AI was capable of.

When it comes to incorrect comparisons I naively created a mental model where AI was just the next iteration of our smart assistant technologies like Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant. Those tools are great for keeping shopping lists but can be infuriating with some of the most basic tasks. This subconsciously created a mental ceiling on my expectations of what ChatGPT and other GenAI tools could do for me.

With these two things combined, my lack of imagination of what to even attempt to use ChatGPT for was in full-effect. I’d dismiss use cases without even attempting them, the way you would dismiss your 8 year old son as a viable helper to move a piano. Anything but the mundane just wasn’t possible.

Getting my feet wet

As the Internet started buzzing more and more about ChatGPT, I would hear a lot of chatter about how awesome it was but without any tangible time-saving use cases for me. I did begin to use it to do things like generate location names for my D&D game and the results were helpful!

Generate a list of 20 names of a cult organization in a fantasy setting that is tasked with preventing demons from entering the world

That prompt responded with a list (cut down for brevity)

1. The Veilwardens 2. Order of the Abyssal Seal 3. Guardians of the Broken Gate 4. The Demonveil Covenant 5. Wardens of the Unseen Lock 6. The Chainbound Order 7. The Seraphic Vanguard 8. Watchers of the Nethergate 9. The Crimson Sigil 10. The Sanctum of Eternal VigilNot bad, but again, a cheap parlor trick in my eyes.

Can ChatGPT help me professionally though?

As the generative AI fervor continued to heat up, I feared becoming a dinosaur. That guy in the office that does things “the old school way” and has the young folk running circles around him. (I already feel that way about Email vs Slack/Teams) I decided to start looking more seriously at ChatGPT.

This week I made a LinkedIn Post asking how people were using AI in their role as managers. It didn’t get a ton of traction but a few articles posted got me thinking of possibilities.

I’ve been working out some performance metrics for my team and I’d been thinking about using a Z-score to create a comparable value for story points completed across people on different teams. (Different teams might have different pointing methods so a direct comparison isn’t fruitful) I wasn’t 100% confident that statistically speaking, what I was trying to do was fair. I asked my wife, who is stronger in statistics than I and she pondered it for a bit before saying “Ask ChatGPT”. It sounded ludicrous to me but what did I have to lose.

Prompt

Can I use the z-score to compare developer stories per sprint for teams that use different story pointing methods

Response

Yes, you can use the z-score to compare developer stories per sprint across teams with different story-pointing methods, but you need to be cautious about how you interpret the results.

Why the Z-Score Could Work

- Standardization – The z-score helps normalize the number of developer stories completed per sprint within each team. This allows you to compare how far each sprint’s performance deviates from that team’s own average, regardless of absolute values.

- Relative Performance – Since different teams may use different story-pointing methods (e.g., Fibonacci vs. T-shirt sizing vs. linear scales), the absolute values might not be directly comparable, but their distributions within each team can be.

Potential Pitfalls

- Different Definitions of “Story” – Some teams might split work into smaller or larger stories, which means a higher count of stories per sprint doesn’t necessarily mean more work was done.

- Variance Differences – If one team has a much more volatile sprint performance (high standard deviation) compared to another, z-score comparisons might exaggerate or downplay certain trends.

- Context Matters – Even with a z-score, a high number of completed stories might not indicate better productivity—it could just mean different estimation practices.

How to Use It Effectively

• Compute z-scores within each team for a fair comparison.

• Look at trends rather than absolute z-score values.

• Complement with other metrics like velocity trends, cycle time, or throughput to get a more holistic view.

It answered my question and my concerns almost perfectly. The one mistake, and this is a prompting mistake, is that it assumed I was using stories completed versus story points completed. But the advice is still sound. Now my creative juices are flowing.

I’ve wanted to do spend analysis on a few of our contracts. I’ve been avoiding it because getting the contract data into a workable format is tedious. Previously I’d dismissed ChatGPT as a viable solution, “it would be more effort than just entering it myself” was my unspoken stance. But now I had the audacity of hope.

I picked a vendor that had some quirks in terms of how the data was structured. A basic line item on the contract consisted of

- Service

- Quantity

- List price

- Sale price

It was also formatted in sections as opposed to all the line items being one after another. The other complication is that the list and sale prices were grouped in bundles, so the sale price would read “$10 per 10k executions” for example. I was just going to throw it at ChatGPT and see what I got.

I uploaded 4 years worth of annual invoices (after upgrading my ChatGPT subscription to the pro plan) and gave the following prompt.

Process the attached PDFs and convert the Committed Services section to a CSV file. The columns should be Service/Feature, Quantity, List Price and Sales Price. Add an additional column named “Contract Year” and fill that columns value with the year taken from the Start Date. Add another column that calculates the total price by multiplying the sales price and the quantity and then multiplying that value by 12

Given my experiences, I thought this was a bold ask. ChatGPT performed flawlessly. A few things that impressed me.

- It was smart enough to understand the “$10 per 10k executions” and convert that to a per execution value for the sake of doing the math.

- The response it gave back indicated that it understood my intent with the math. Part of the confirmation response was “Total Price (calculated as Quantity × Sales Price × 12 to reflect the annual cost)” It was smart enough to infer that the billing details were monthly and I wanted an annual total.

I downloaded my CSV, checked the totals against the invoices and they were spot on. I launched Excel, ready to import my new data and get to analyzing when I realized that my lack of imagination was still getting in my way. I went back to the ChatGPT prompt.

Analyze the attached CSV and describe for me any trends that you find. Also tell me what is the biggest driver of my spend year over year

It came back with a table (which I can’t share) that listed my annual spend per contract year, another table with my top line item spend per year and then a narrative about that year with inferred reasons for that spend. (“X became the highest cost driver, showing a move towards Y”) It recognized that the increase in specific line item categories showed an overall shift of investment and focus in those areas. It also performed a linear regression-based forecast on my top spending line items for the next three years. It also identified areas of negative growth in terms of usage/adoption and suggested identifying what was driving that trend and if it’s expected, to accelerate it to reduce costs.

To put a bow on it I asked ChatGPT one more question. I personally have estimated a total spend on the annual contract value where once we cross it, we should begin evaluating bringing that work in-house. (Eventually, it can become cheaper to run things yourself once you’ve hit a certain scale) I asked ChatGPT when it projected I would hit this number and it projected late 2027 with an estimated annual dollar amount. This was all done in under 15 minutes.

Next Steps

I’m now convinced that ChatGPT needs to be part of my toolbox. Instead of wasting 30 minutes of my time and then moving to ChatGPT for some tasks, I’ll start there, uninhibited by expectations, and see what magic I can wrought out.

Of course ChatGPT still has its deficiencies but we shouldn’t assume those are the norm. I asked it to generate a slide for me and regardless of the efficacy of my prompt, ChatGPT still doesn’t know how to spell words in images.

Nothing is perfect. But it can still be useful!

-

Quick Review of Upstream by Dan Heath

Finished reading: Upstream by Dan Heath 📚

I really enjoyed this book and it has a number of great case studies that are generally interesting even outside the context of the subject matter. The book is structured in a way to make it digestible and applicable to a wide variety of use cases.

One of the more useful takeaways for me was the idea of “ghost victories”.

there is a separation between (a) the way we’re measuring success and (b) the actual results we want to see in the world, we run the risk of a “ghost victory”: a superficial success that cloaks failure.

The book goes into the various types of ghost victories as well as a series of questions to help “pre-game” against ghost victories. Very useful stuff.

A famous example of a ghost victory would be the drop in crime in New York City during the 90’s. The CompStat program and the leadership of Bill Bratton were hearlded as key change agents for reducing crime in NYC. The problem is that crime everywhere in the US, not just NYC, was dropping in the 90’s. How does a program in NYC magically have the same effect as an unknown source in Boston? We don’t know what caused the drop in crime in the 90’s but few still believe CompStat was the cause.

The book is filled with examples like this, some of which will leave your mouth open in awe. If you’re looking for a book about effecting change in an organization, Upstream and Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard are two great options.

-

Carry-On, 2024 - ★★★

There's something about the majority of Netflix original films I've seen that I can't quite put my finger on. No matter the budget or the star studded cast, they can't help but escape the feeling of a made for TV movie. They're perfectly passable as part of the $19.99 all you can eat buffet but if you paid for it as an individually priced entree, you'd be looking for a refund. Carry-On fully embodies this metaphor.

Without spoiling the film, the basic premise is that a TSA agent is coaxed, by threat of harm to his pregnant girlfriend, to aide in a plot to smuggle a bag with unknown contents through the TSA baggage check.

Considering the premise, you'd expect a fast paced thriller that quickly dumps you into the action. Instead, the film spends an unreasonable amount of time setting up the backstory for the main character, played by Taron Egerton. Once the backstory is established and the main thrust of the plot begins the story still drags on as the villain, played by Jason Bateman, establishes his dominance of skill, preparation and intelligence over the main character. Only about 50 minutes into the film do things begin to pick up. From there you're on a mostly linear thrill ride that doesn't bore but at the same time doesn't excel in any meaningful way.

As a rule, I love anything with Jason Bateman in it. There's something about his comedic delivery and timing that just fits with every role I see him in. I was intrigued to see him play a villain and to see that comedic timing work in a villainous capacity. But aside from a couple of great moments, Bateman's charm has been largely stripped away, leaving in its place a fairly run of the mill villain.

As part of the Netflix bonanza, the movie is passable. It's PG-13 so that gives it a boost as a family movie night option. I can think of worse ways to kill 2 hours but there's no need to rush to see this one.

-

Came across an old photo tonight. Church boy getting ready for service!

-

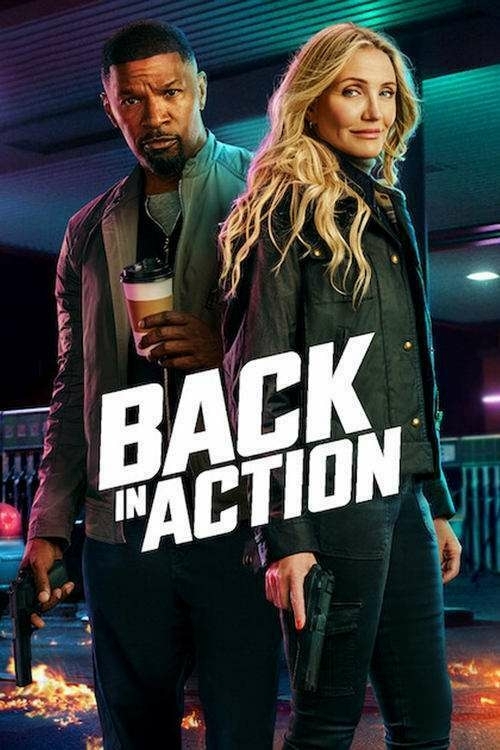

Back in Action, 2025 - ★★★

A fun family friendly action flick that you may have seen in various iterations. It doesn’t add anything new to the trope but Jamie Foxx and Cameron Diaz have a surprising comedic synergy.

-

Weird that the last post didn’t include the photo. A bug in the mobile app maybe?